A Matter of Life and Death: When Religion and Medicine Clash

Consider the challenges of balancing different beliefs while making ethical decisions.

Jane the Jehovah's Witness

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, St. Christopher's Hospital for Children admits a young girl, Jane, into its care. Jane’s hemoglobin has fallen to three grams per deciliter, she is bleeding out—she is dying. She is a Jehovah’s Witness.

Jehovah’s Witnesses believe from scripture that he who eats or drinks the blood of another is condemned to hell. Jane’s parents are her proxy; they don't want the blood transfusion, so she refuses it. At this point, the surgeons expect her to die.

The hospital calls in a bioethicist. There might be a solution. A 1944 Supreme Court case Prince v. Massachusetts ruled that parents do not necessarily have absolute authority and can be restricted if it is in the best interest of a child. Jane can receive a transfusion—all the ethicist needs to do is talk to the 24/7 judge on call and get a court injunction (a court order requiring a person to do a specific action) to transfuse.

But he doesn’t. “Before we do this, we have to offer her one more thing ethically.” What did they offer Jane?

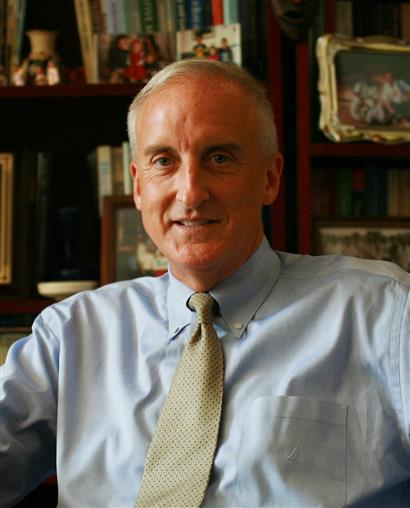

Enter Dr. Peter Clark

The bioethicist called in was Dr. Peter Clark, a professor of Medical Ethics, a director of the Institute of Clinical Bioethics at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, a priest, and a bioethical consultant for numerous Pennsylvania hospitals and a hospital in Palestine. Simply put, he’s an expert in all things ethics-related.

Clark’s research and work covers a wide spread of subjects but has recently dealt with three main areas.

- Orthodox Jews’ definition of death. In the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, death occurs when the heart stops, therefore exempting them from the brain death criteria. Clark explained how in Orthodox Jewish patients, in particular, Hasidic Jews, even after apnea tests pronounced the patient brain dead, doctors would maintain the patients on a ventilator until their heart stopped in accordance with their religion.

- Traditional Muslims must be told that heparin and Lovenox—which are blood thinners—are pork-based. “It’s then up to the patient’s Imam [the prayer leader of a mosque] to make the decision whether they can use it or not,” Clark said.

- The ethical implications of frozen embryos from a Catholic perspective. “The church believes that frozen embryos are persons in suspended animation. So, what do you do with them?” Clark asked. “I mean, we have a million frozen embryos right now. Most families do not want them… and they have stopped paying for the freezing.” These circumstances raise some questions: who now owns the embryo? What happens to them if no one claims them?

Answers to these kinds of questions might depend on a doctor’s, even an institution’s, own beliefs. St. Joseph’s University, as a Catholic institution, must abide by the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, which dictates certain things St. Joe’s can and cannot do. For example, Directive Thirteen requires that particular care be taken "to provide and to publicize opportunities for patients or residents to receive the Sacrament of Penance [confession];” Directive Sixty forbids any Catholic health care institution from “condoning or participate in euthanasia or assisted suicide in any way.”

But even within one religion, there can be differences in opinion regarding ethics, ranging from small variations in practice to complete disagreement. One example involves discrepancies in different Imams’ interpretations of the Quran on whether a Muslim patient could receive heparin or Lovenox. Clark recalled two such cases: one Imam said yes, one said no. Regarding the embryo issue from earlier, Clark wrote a paper in 2008 suggesting the embryos should be put up for adoption. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, however, wrote in 2022 that “proposals for ‘adoption’ of abandoned or unwanted frozen embryos are found to pose problems, because the Church opposes use of the gametes or bodies of others who are outside the marital covenant for reproduction.” These kinds of differences of opinion can spark healthcare controversies.

Remember Jane?

By now, you’re either still speculating on what Clark offered the girl from the first scenario, or maybe you’ve completely forgotten about it. Either way, what did Clark offer her?

He extended her the right of judicial emancipation. This way, she could make her own decision about whether she wanted a transfusion or not, without interference from her parents. “A judge came in, went into her room and spoke to her for an hour, walked out of the room and decided she was an emancipated minor,” Clark said. The girl decided, as a legal independent, to refuse the transfusion. She bled out and died.

“The surgeons were furious that we even offered that option,” Clark remembered, “But I think you have to offer that option ethically to her. To her, it's an issue of values. Which value to her took priority, sanctity of life or spiritual life? And for her, the spiritual life had a priority over the side of the sanctity of life. So, even though they were angry with it, I think we did the right thing.”

To her, it's an issue of values. Which value to her took priority, sanctity of life or spiritual life?

The Jordanian Royal Family

A couple comes into St. Christopher’s with their 13-year-old son. Dr. Clark and the other doctors suspect they are part of the Jordanian royal family. The parents report bleeding from their son’s penis, and that his classmates laugh at him in school because his breasts are developing. After a workup, the doctors discover the child is reproductively a female, but outwardly a male. The bleeding from the penis appeared to be menstruation and the breasts are in the process of breast development. Upon hearing this, the father demands a hysterectomy (removal of the uterus), an oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) and a radical mastectomy (removal of the breasts). It would be a risky set of procedures if a surgeon completed them all at once. The father would not allow any doctors to talk to the boy. He just wanted the surgeries done quickly because of the family’s limited visa to stay in the U.S.

Does the child have a right to assent to the surgeries? Could the doctors ethically do the surgeries without his assent? The father informed the doctors that he would not bring his son back home as his daughter. Money was clearly not an issue for him. After the doctors told the father that there was a high probability his son, if he remained a boy, would be homosexual because of the hormones, the father scoffed. He said, “Don't worry about that, there are no homosexuals in Jordan.” The father complicated matters more, adding, “If you don't do the surgery, we'll go to London and have it done there.” Should the hospital do the surgery or not?

After five days of deliberation, the hospital decided against the surgeries. They gave the family the option of giving the child Leuprolide, a puberty blocker that would decrease any development, until he was old enough to give consent. “The father said absolutely not, took his family and they left and… I presume he had the surgeries in London,” Clark said. This situation raised multiple religious and cultural concerns, and created an ideological divide in the hospital. The financial department advocated for the surgeries because the father was willing to build a wing in the hospital. “The bottom line is money in many ways,” Clark added, “But it was really the ethics committee that stood up and said, ‘No, we won't do it. We won't consent.’”

What Can We Do?

Doctors face these situations that have no clear moral answer, so they need to educate themselves about cultural issues, religious exemptions and options they can provide patients. "I just think we have to do a better job with cultural sensitivity, religious sensitivity… and ethnic sensitivity, and I'm not sure the medical profession is doing a great job on that, to be honest,” Clark says.

The Solution

So, how can the medical profession improve its handling of ethically ambiguous circumstances? Medicine must improve from an educational perspective. Doctors simply need to have ethics training.

Responses from a University of New Mexico School of Medicine survey given to 200 medical students and 136 residents indicated the need for “more academic attention directed at practical ethical and professional dilemmas present during training and the practice of medicine.” Medical students and doctors who have taken ethics classes and done ethics rounds report the education helpful in difficult situations.

While the presence of ethics education in medical schools has considerably increased in recent years, how it is taught greatly varies from institution to institution. Most attempts at improving medical ethics education occurs locally, with individual schools making decisions about their own curricula. This can cause inconsistencies in ethics education because the resources available at institutions vary widely. "Some places have one part-time person, and others have robust ethics programs with a dozen people," says Dr. Michael Green, one of the authors of a report that evaluated the state of medical ethics education in the U.S in 2015.

This report found that most institutions provide ethics education only during the first two years of medical school—this, too, only in a classroom setting, meaning students often receive very little practical ethics training during residency. Rather than painting "ethics" in broad strokes by teaching ethical principles, the medical education system should devote more effort into teaching students how to behave ethically in specific situations. Not only will up-to-date medical ethics education train doctors to be more sensitive, but it is also a good way to legally protect a physician and prevent malpractice suits.

What follows from this is also helping future doctors understand and navigate the practicalities of law in medicine. Some surveys show that practicing physicians have a poor and often incomplete understanding of basic principles of malpractice law. One study finds practicing physicians have an incomplete understanding of the fundamentals of malpractice law. U.S. medical education is at fault: only 37% of U.S. medical schools offer formalized coursework dealing with the legal or regulatory issues in medicine, as the AMA Journal of Ethics finds. The consequences of doctors' misunderstanding of the law are twofold.

- It fosters divide and distrust between physicians and legal/regulatory systems.

- Physicians will make misguided risk-management decisions, leading to the practice of defensive medicine. Defensive medicine carries with it financial costs and burdens to the patient, such as unnecessary testing or more false-positives.

To effectively integrate legal considerations into medical education, medical curricula should enable students to identify potential areas of conflict between medical practice and law. Combining practical ethics education with legal training can help students develop a deeper understanding of how the legal system operates and help them avoid legal pitfalls. Such an approach can promote greater awareness and reduce self-protective decision-making in medical practice.

In an increasingly complex and dynamic world, doctors be forced to think about the tough questions. Sometimes the right answer won't be clear right away. Sometimes the right answer will be something they don't personally agree with. Sometimes, there won't be a right answer. But when a young girl with a hemoglobin of three—who happens to be a Jehovah’s Witness—is admitted to their hospital, they will know what their options are.